This is a guest post by Mailtrap.io team. The original post on Sending emails with Django was published at Mailtrap's blog.

Some time ago, we discovered how to send an email with Python using smtplib, a built-in email module. Back then, the focus was made on the delivery of different types of messages via SMTP server. Today, we prepared a similar tutorial but for Django. This popular Python web framework allows you to accelerate email delivery and make it much easier. And these code samples of sending emails with Django are going to prove that.

A simple code example of how to send an email

Let's start our tutorial with a few lines of code that show you how simple it is to send an email in Django.

Import send_mail at the beginning of the file

from django.core.mail import send_mail

And call the code below in the necessary place.

send_mail(

"That's your subject",

"That's your message body",

"from@yourdjangoapp.com",

["to@yourbestuser.com"],

fail_silently=False,

)

These lines are enclosed in the django.core.mail module that is based on smtplib. The message delivery is carried out via SMTP host, and all the settings are set by default:

EMAIL_HOST: "localhost"EMAIL_PORT: 25EMAIL_HOST_USER: (Empty string)EMAIL_HOST_PASSWORD: (Empty string)EMAIL_USE_TLS: FalseEMAIL_USE_SSL: False

You can learn other default values here. Most likely you will need to adjust them. Therefore, let's tweak the settings.py file.

Setting up

Before actually sending your email, you need to set up for it. So, let's add some lines to the settings.py file of your Django app.

EMAIL_BACKEND = "django.core.mail.backends.smtp.EmailBackend"

EMAIL_HOST = "smtp.yourserver.com"

EMAIL_PORT = "<your-server-port>"

EMAIL_HOST_USER = "your@djangoapp.com"

EMAIL_HOST_PASSWORD = "your-email account-password"

EMAIL_USE_TLS = True

EMAIL_USE_SSL = False

EMAIL_HOST is different for each email provider you use. For example, if you use Gmail SMTP server, you'll have EMAIL_HOST = "smtp.gmail.com". Also, validate other values that are relevant to your email server. Eventually, you need to choose the way to encrypt the mail and protect your user account by setting the variable EMAIL_USE_TLS or EMAIL_USE_SSL. If you have an email provider that explicitly tells you which option to use, then it is clear. Otherwise, you may try different combinations using True and False operators. Mind that only one of these options can be set to True.

EMAIL_BACKEND tells Django which custom or predefined email backend will work with EMAIL_HOST. You can set up this parameter as well.

SMTP email backend

In the example above, EMAIL_BACKEND is specified as django.core.mail.backends.smtp.EmailBackend. It is the default configuration that uses SMTP server for email delivery. Defined email settings will be passed as matching arguments to EmailBackend.

Unspecified arguments default to None.

Besides django.core.mail.backends.smtp.EmailBackend, you can use:

django.core.mail.backends.console.EmailBackend - the console backend that composes the emails that will be sent to the standard output. Not intended for production use.django.core.mail.backends.filebased.EmailBackend - the file backend that creates emails in the form of a new file per each new session opened on the backend. Not intended for production use.django.core.mail.backends.locmem.EmailBackend - the in-memory backend that stores messages in the local memory cache of django.core.mail.outbox. Not intended for production use.django.core.mail.backends.dummy.EmailBackend - the dummy cache backend that implements the cache interface and does nothing with your emails. Not intended for production use.- Any out-of-the-box backend for Amazon SES, Mailgun, SendGrid, and other services.

How to send emails via SMTP

Once you have that configured, all you need to do to send an email is to import the send_mail or send_mass_mail function from django.core.mail. These functions differ in the connection they use for messages. The send_mail uses a separate connection for each message. The send_mass_mail opens a single connection to the mail server and is mostly intended to handle mass emailing.

Sending email with send_mail

This is the most basic function for email delivery in Django. It comprises four obligatory parameters to be specified: subject, message, from_email, and recipient_list.

In addition to them, you can adjust the following:

-

auth_user: If EMAIL_HOST_USER has not been specified, or you want to override it, this username will be used to authenticate to the SMTP server.

-

auth_password: If EMAIL_HOST_PASSWORD has not been specified, this password will be used to authenticate to the SMTP server.

-

connection: The optional email backend you can use without tweaking EMAIL_BACKEND.

-

html_message: Lets you send multipart emails.

-

fail_silently: A boolean that controls how the backend should handle errors. If True - exceptions will be silently ignored. If False - smtplib.SMTPException will be raised.

For example, it may look like this:

from django.core.mail import send_mail

send_mail(

subject="That's your subject",

message="That's your message body",

from_email="from@yourdjangoapp.com",

recipient_list=["to@yourbestuser.com"],

auth_user="Login",

auth_password="Password",

fail_silently=False,

)

Other functions for email delivery include mailadmins and mailmanagers. Both are shortcuts to send emails to the recipients predefined in ADMINS and MANAGERS settings, respectively. For them, you can specify such arguments as subject, message, fail_silently, connection, and html_message. The from_email argument is defined by the SERVER_EMAIL setting.

What is EmailMessage for?

If the email backend handles the email sending, the EmailMessage class answers for the message creation. You'll need it when some advanced features like BCC or an attachment are desirable. That's how an initialized EmailMessage may look:

from django.core.mail import EmailMessage

email = EmailMessage(

subject="That's your subject",

body="That's your message body",

from_email="from@yourdjangoapp.com",

to=["to@yourbestuser.com"],

bcc=["bcc@anotherbestuser.com"],

reply_to=["whoever@itmaybe.com"],

)

In addition to the EmailMessage objects you can see in the example, there are also other optional parameters:

connection: defines an email backend instance for multiple messages. attachments: specifies the attachment for the message.headers: specifies extra headers like Message-ID or CC for the message. cc: specifies email addresses used in the "CC" header.

The methods you can use with the EmailMessage class are the following:

send: get the message sent.message: composes a MIME object (django.core.mail.SafeMIMEText or django.core.mail.SafeMIMEMultipart).recipients: returns a list of the recipients specified in all the attributes including to, cc, and bcc.attach: creates and adds a file attachment. It can be called with a MIMEBase instance or a triple of arguments consisting of filename, content, and mime type.attach_file: creates an attachment using a file from a filesystem. We'll talk about adding attachments a bit later.

How to send multiple emails

To deliver a message via SMTP, you need to open a connection and close it afterward. This approach is quite awkward when you need to send multiple transactional emails. Instead, it is better to create one connection and reuse it for all messages. This can be done with the send_messages method. Check out the following example:

from django.core import mail

connection = mail.get_connection()

connection.open()

email1 = mail.EmailMessage(

"That's your subject",

"That's your message body",

"from@yourdjangoapp.com",

["to@yourbestuser1.com"],

connection=connection,

)

email1.send()

email2 = mail.EmailMessage(

"That's your subject #2",

"That's your message body #2",

"from@yourdjangoapp.com",

["to@yourbestuser2.com"],

)

email3 = mail.EmailMessage(

"That's your subject #3",

"That's your message body #3",

"from@yourdjangoapp.com",

["to@yourbestuser3.com"],

)

connection.send_messages([email2, email3])

connection.close()

What you can see here is that the connection was opened for email1, and send_messages uses it to send emails #2 and #3. After that, you close the connection manually.

How to send multiple emails with sendmassmail

send_mass_mail is another option to use only one connection for sending different messages.

message1 = (

"That's your subject #1",

"That's your message body #1",

"from@yourdjangoapp.com",

["to@yourbestuser1.com", "to@yourbestuser2.com"]

)

message2 = (

"That's your subject #2",

"That's your message body #2",

"from@yourdjangoapp.com",

["to@yourbestuser2.com"],

)

message3 = (

"That's your subject #3",

"That's your message body #3",

"from@yourdjangoapp.com",

["to@yourbestuser3.com"],

)

send_mass_mail((message1, message2, message3), fail_silently=False)

Each email message contains a datatuple made of subject, message, from_email, and recipient_list. Optionally, you can add other arguments that are the same as for send_mail.

How to send an HTML email

When the article was published, the latest Django official version was 2.2.4. All versions starting from 1.7 let you send an email with HTML content using send_mail like this:

from django.core.mail import send_mail

subject = "That's your subject"

html_message = render_to_string("mail_template.html", {"context": "values"})

plain_message = strip_tags(html_message)

from_email = "from@yourdjangoapp.com>"

to = "to@yourbestuser.com"

mail.send_mail(subject, plain_message, from_email, [to], html_message=html_message)

Older versions users will have to mess about with EmailMessage and its subclass EmailMultiAlternatives. It lets you include different versions of the message body using the attach_alternative method. For example:

from django.core.mail import EmailMultiAlternatives

subject = "That's your subject"

from_email = "from@yourdjangoapp.com>"

to = "to@yourbestuser.com"

text_content = "That's your plain text."

html_content = """<p>That's <strong>the HTML part</strong></p>"""

message = EmailMultiAlternatives(subject, text_content, from_email, [to])

message.attach_alternative(html_content, "text/html")

message.send()

How to send an email with attachments

In the EmailMessage section, we've already mentioned sending emails with attachments. This can be implemented using attach or attach_file methods. The first one creates and adds a file attachment through a triple of arguments - filename, content, and mime type. The second method uses a file from a filesystem as an attachment. That's how each method would look like in practice:

message.attach("Attachment.pdf", file_to_be_sent, "file/pdf")

or

message.attach_file("/documents/Attachment.pdf")

Custom email backend

Obviously, you're not limited to the abovementioned email backend options and are able to tailor your own. For this, you can use standard backends as a reference. Let's say you need to create a custom email backend with the SMTP_SSL connection support required to interact with Amazon SES. The default SMTP backend will be the reference. First, add a new email option to settings.py.

AWS_ACCESS_KEY_ID = "your-aws-access-key-id"

AWS_SECRET_ACCESS_KEY = "your-aws-secret-access-key"

AWS_REGION = "your-aws-region"

EMAIL_BACKEND = "your_project_name.email_backend.SesEmailBackend"

Make sure that you are allowed to send emails with Amazon SES using these AWS_ACCESS_KEY_ID and AWS_SECRET_ACCESS_KEY (or an error message will tell you about it :D)

Then create a file your_project_name/email_backend.py with the following content:

import boto3

from django.core.mail.backends.smtp import EmailBackend

from django.conf import settings

class SesEmailBackend(EmailBackend):

def __init__(

self,

fail_silently=False,

**kwargs

):

super().__init__(fail_silently=fail_silently)

self.connection = boto3.client(

"ses",

aws_access_key_id=settings.AWS_ACCESS_KEY_ID,

aws_secret_access_key=settings.AWS_SECRET_ACCESS_KEY,

region_name=settings.AWS_REGION,

)

def send_messages(self, email_messages):

for email_message in email_messages:

self.connection.send_raw_email(

Source=email_message.from_email,

Destinations=email_message.recipients(),

RawMessage={"Data": email_message.message().as_bytes(linesep="\r\n")}

)

This is the minimum needed to send an email using SES. Surely you will need to add some error handling, input sanitization, retries, etc. but this is out of our topic.

You might see that we have imported boto3 at the beginning of the file. Don't forget to install it using a command

It's not necessary to reinvent the wheel every time you need a custom email backend. You can find already existing libraries, or just receive SMTP credentials in your Amazon console and use default email backend.

Sending emails using SES from Amazon

So far, you can benefit from several services that allow you to send transactional emails at ease. If you can't choose one, check out our blogpost about Sendgrid vs. Mandrill vs. Mailgun. It will help a lot. But today, we'll discover how to make your Django app send emails via Amazon SES. It is one of the most popular services so far. Besides, you can take advantage of a ready-to-use Django email backend for this service - django-ses.

Set up the library

You need to execute pip install django-ses to install django-ses. Once it's done, tweak your settings.py with the following line:

EMAIL_BACKEND = "django_ses.SESBackend"

AWS credentials

Don't forget to set up your AWS account to get the required credentials - AWS access keys that consist of access key ID and secret access key. For this, add a user in Identity and Access Management (IAM) service. Then, choose a user name and Programmatic access type. Attach AmazonSESFullAccess permission and create a user. Once you've done this, you should see AWS access keys. Update your settings.py:

AWS_ACCESS_KEY_ID = "********"

AWS_SECRET_ACCESS_KEY = "********"

Email sending

Now, you can send your emails using django.core.mail.send_mail:

from django.core.mail import send_mail

send_mail(

"That's your subject",

"That's your message body",

"from@yourdjangoapp.com",

["to@yourbestuser.com"]

)

django-ses is not the only preset email backend you can leverage. At the end of our article, you'll find more useful libraries to optimize email delivery of your Django app. But first, a step you should never send emails without.

Testing email sending in Django

Once you've got everything prepared for sending email messages, it is necessary to do some initial testing of your mail server. In Python, this can be done with one command:

python -m smtpd -n -c DebuggingServer localhost:1025

It allows you to send emails to your local SMTP server. The DebuggingServer feature won't actually send the email but will let you see the content of your message in the shell window. That's an option you can use off-hand.

Django's TestCase

TestCase is a solution to test a few aspects of your email delivery. It uses django.core.mail.backends.locmem.EmailBackend, which, as you remember, stores messages in the local memory cache - django.core.mail.outbox. So, this test runner does not actually send emails. Once you've selected this email backend

EMAIL_BACKEND = "django.core.mail.backends.locmem.EmailBackend"

you can use the following unit test sample to test your email sending capability.

from django.core import mail

from django.test import TestCase

class EmailTest(TestCase):

def test_send_email(self):

mail.send_mail(

"That's your subject", "That's your message body",

"from@yourdjangoapp.com", ["to@yourbestuser.com"],

fail_silently=False,

)

self.assertEqual(len(mail.outbox), 1)

self.assertEqual(mail.outbox[0].subject, "That's your subject")

self.assertEqual(mail.outbox[0].body, "That's your message body")

This code will test not only your email sending but also the correctness of the subject and message body.

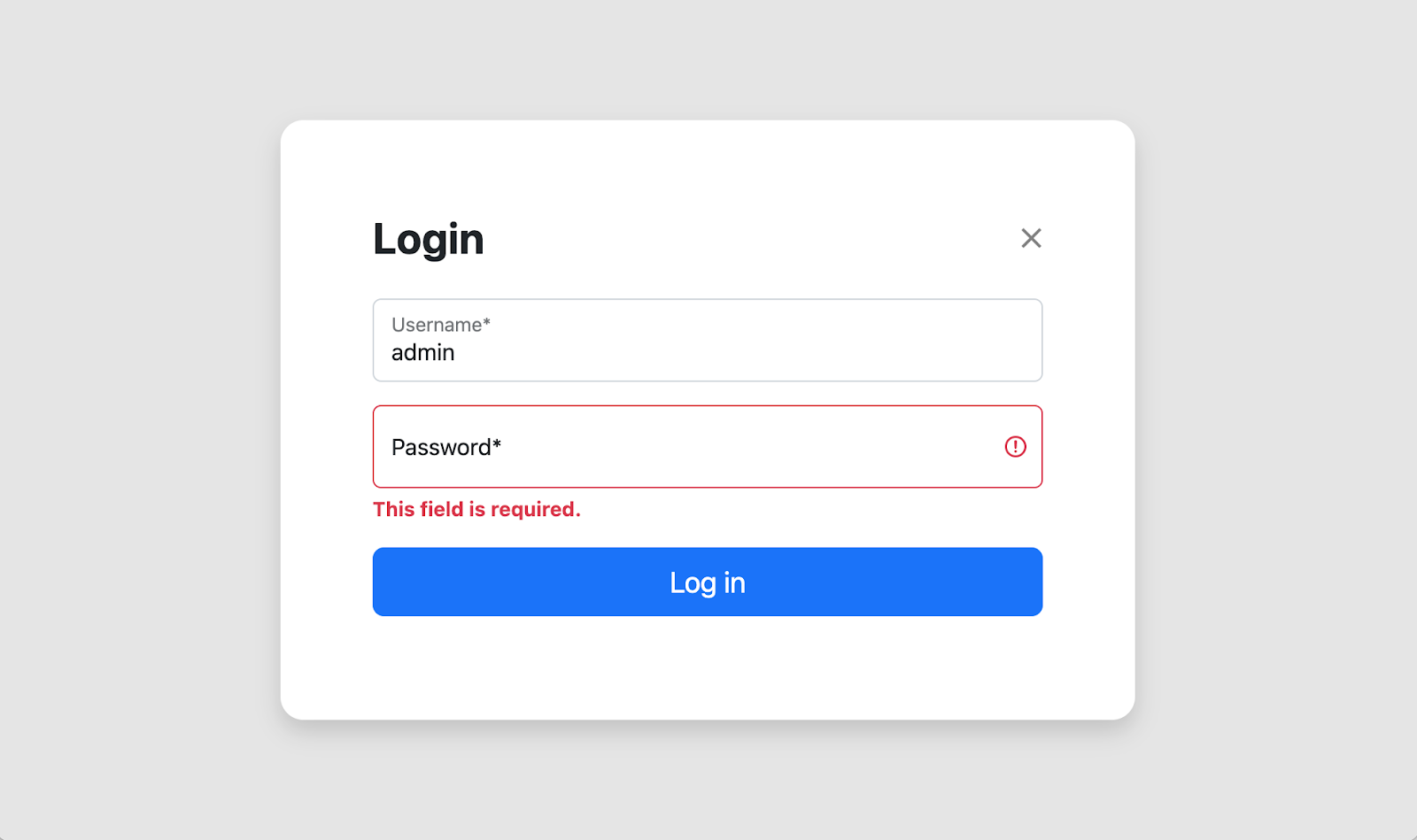

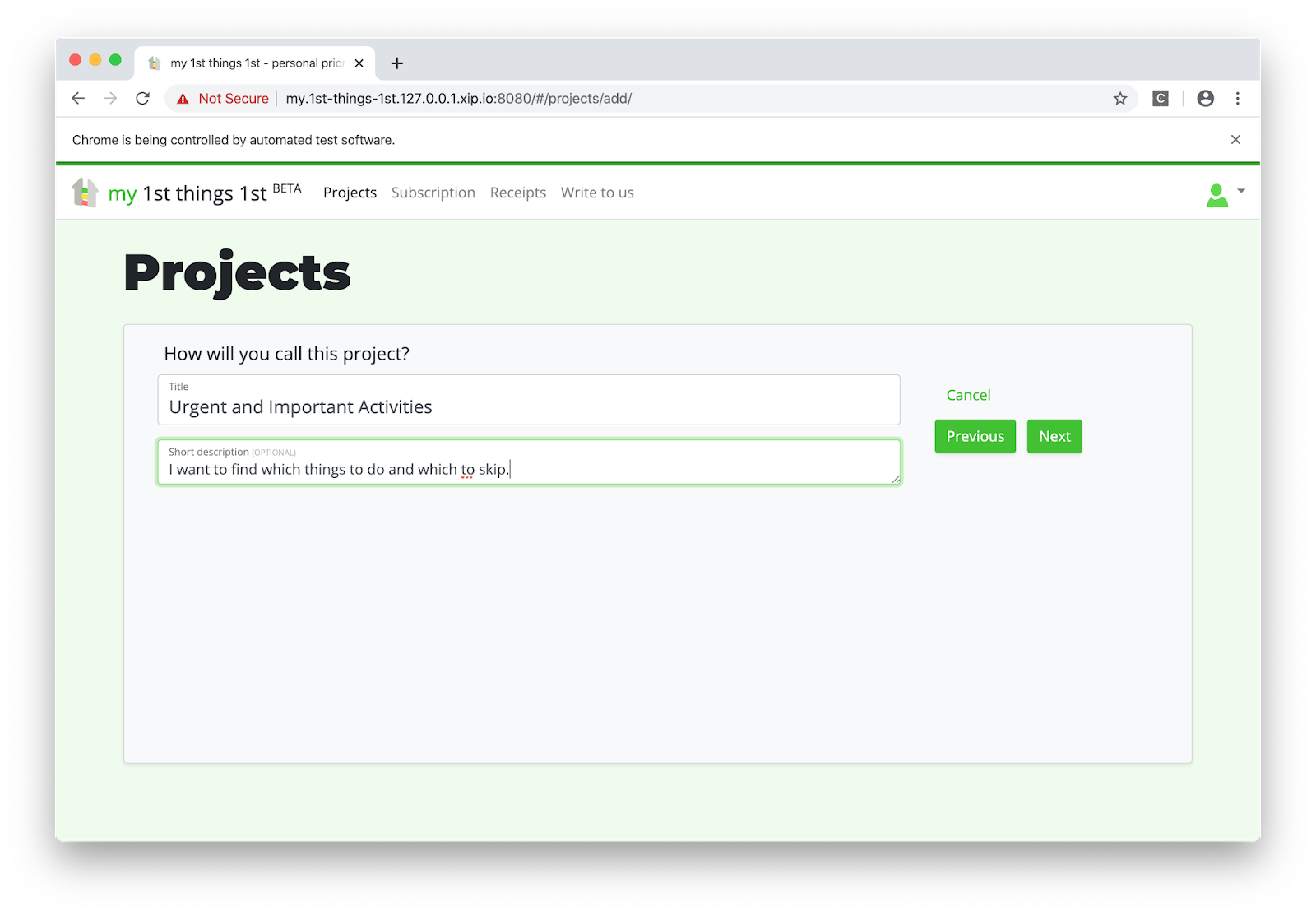

Testing with Mailtrap

Mailtrap can be a rich solution for testing. First, it lets you test not only the SMTP server but also the email content and do other essential checks from the email testing checklist. Second, it is a rather easy-to-use tool.

All you need to do is to copy the SMTP credentials from your demo inbox and tweak your settings.py. Or you can just copy/paste these four lines from the Integrations section by choosing Django in the pop-up menu.

EMAIL_HOST = "smtp.mailtrap.io"

EMAIL_HOST_USER = "********"

EMAIL_HOST_PASSWORD = "*******"

EMAIL_PORT = "2525"

After that, feel free to send your HTML email with an attachment to check how it goes.

from django.core.mail import EmailMultiAlternatives

from django.template.loader import render_to_string

subject = "That's your subject"

html_message = render_to_string("mail_template.html", {"context": "values"})

plain_message = strip_tags(html_message)

from_email = "from@yourdjangoapp.com"

to_email = "to@yourbestuser.com"

message = EmailMultiAlternatives(subject, plain_message, from_email, [to_email])

message.attach_alternative(html_message, "text/html")

message.attach_file("/documents/Attachment.pdf")

message.send()

If there is no message in the Mailtrap Demo inbox or there are some issues with HTML content, you need to polish your code.

Django email libraries to simplify your life

As a conclusion to this blog post about sending emails with Django, we've included a brief introduction of a few libraries that will facilitate your email workflow.

django-anymail

This is a collection of email backends and webhooks for numerous famous email services, including SendGrid, Mailgun, and others. django-anymail works with django.core.mail module and normalizes the functionality of transactional email service providers.

django-mailer

django-mailer is a Django app you can use to queue the email sending. With it, scheduling your emails is much easier.

django-post_office

With this app, you can send and manage your emails. django-post_office offers many cool features like asynchronous email sending, built-in scheduling, multiprocessing, etc.

django-templated-email

This app is about sending templated emails. In addition to its own functionalities, django-templated-email can be used in tow with django-anymail to integrate transactional email service providers.

django-mailbox

You might use django-mailbox if you need to import messages from local mailboxes, POP3, IMAP, or directly receive messages from Postfix or Exim4.

We hope that this small list of packages will facilitate your email workflow. You can always find more apps at Django Packages.

Cover Photo by Chris Ried